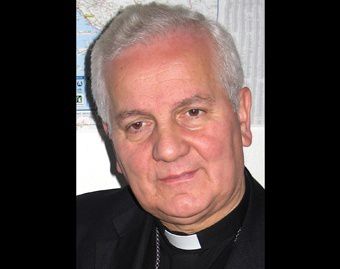

In the run-up to national elections, the bishops of Bosnia and Herzegovina are encouraging the nation's citizens to vote for the rule of law, in hopes of bringing the country out of the instability which sparked violent protests earlier this year. “We need more justice, reconciliation and willingness to work together. We bishops have therefore invited everyone to go to the polls to cast their vote for law and justice and to make sure the country does not get stuck in this disastrous situation,” Bishop Franjo Komarica of Banja Luka told Aid to the Church in Need Oct. 7. Bosnia and Herzegovina will hold national elections Oct. 12, for both members of the bicameral parliament and for the three-member presidency. The Bosnian presidency is a four-year term, with a rotating chairmanship among the members. One member of the presidency is elected from each of Bosnia and Herzegovina's main ethnic groups: a Bosniak, a Croat, and a Serb. Ethno-religious tensions have historically contributed much to instability in the country. Following its independence upon the break-up of Yugoslavia, the country was embroiled in the Bosnian War from 1992 to 1995 in which genocide and ethnic cleansing took place. The Muslim Bosniaks constitute some 48 percent of the population; Orthodox Serbs 37 percent; and Catholic Croats 15 percent. Bishop Komarica is concerned that the instability in his country could radicalize some factions there. “There are people here who could exploit the instability,” he said. “And we mustn't ignore the dark clouds arising to the south east. Destructive, radical forces from the Arab world can very easily settle and flourish here.” He said that Bosnians “are living in an absurd situation.” “Bosnia-Herzegovina is not moving forward, either politically or economically. The country has a number of constitutions which obstruct one another. The number of ministers is astronomical, an indulgence which no other nation allows itself. The people are longing for a new organization of the state.” In February, protestors in several cities, including Banja Luka, Tuzla, and Sarajevo attacked government buildings, setting fire to them. Hundreds were injured, and police used rubber bullets, tear gas, and water cannons to quell the protests. Srecko Latal, of Social Overview Service in Sarajevo, told The New York Times in February that “we haven’t seen violent scenes like this since the war in the 1990s. People are fed up with what has become total political chaos in Bosnia, with infighting over power, a dire economic situation and a feeling that there is little hope for the future. The protests are a wake-up call for the international community not to disengage from Bosnia.” Bosnians' complaints include existing unemployment — between 40 and 50 percent — and the protests were sparked by factory closings in Tuzla. Unemployment rates are higher among the youth, with nearly 75 percent unable to find work. Bosnia and Herzegovina's per capita GDP, adjusted for purchasing power, is less than $9,000. In Transparency International's 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index, Bosnia and Herzegovina ranked 72 — tied with Brazil, Serbia, and South Africa — out of 175 rankings. Its ranking suggests it is slightly more corrupt than Bulgaria and Tunisia, and slightly less corrupt than Italy and Romania. In the face of these problems, Bishop Komarica stressed his country's need for political reform, urging the greater international involvement, particularly from the European Union — which Bosnia and Herzegovina is trying to join.