The house lights dimmed and the action of “The Last Confession,” playing in a limited run at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles, immediately made me think of New York Yankees great Yogi Berra. “It’s déjà vu all over again.”

The play chronicles the fictional life of a real person, Giovanni Cardinal Benelli, and the election and untimely death of Pope John Paul I. It made me flashback to another play from another era. That piece of stagecraft was called “The Deputy” and it painted a rather unpleasant, unfair and unmerited portrait of Pope Pius XII as a villainous Nazi sympathizer.

“The Last Confession” uses the dramatic device of a confession of a dying and guilt-ridden Cardinal Benelli to portray the inner workings of a corrupt Church absolutely teeming with worldly and debauched leaders. The driving force of the drama is the election of John Paul I and the almost instantaneous negative response to it from the “reactionary” forces within the Vatican.

The play, like “The Deputy,” uses real people who, for the most part, are no longer around to defend themselves. The least spiritually empty vessel in the cast is the protagonist Cardinal Benelli, played with kinetic energy by excellent British actor David Suchet, best known for playing Hercule Poirot in the long running BBC series. But the fictionalized Benelli’s spirituality is brutally conflicted with heart wrenching doubt — a common trope I’ve seen in countless plays, movies and television where the only “good” Catholic is the “bad” Catholic.

Even before the house lights went out I had an uneasy feeling after reading author Roger Crane’s backgrounder in the theater program. First, it was so sure of itself in the facts which, even the most crazed conspiracy theorist has to admit, are spotty. An unlikely (as if there is ever a likely one) man is elected pope and reigns for a mere 33 days, and his death is handled poorly by a host of Vatican officials. There are 15 scenarios for every botched inconsistency in the reporting of John Paul I’s death, but the playwright fixates on only the most sensational and outrageous scenario.

Crane instructs us that John Paul I had to be replaced because of his joyful adherence to Vatican II. The playwright never explains what possessed the evil conspirators who murdered John Paul I to replace him with one of the key architects of Vatican II, Karol Wojtyla.

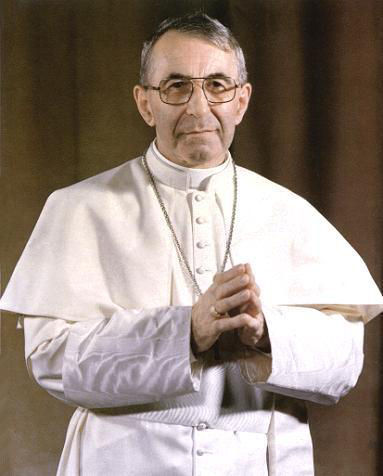

The bulk of this two-and-a-half-hour production revolves around John Paul I, who speaks in very 21st century Catholic-lite language. He is not a bumbler, but just an innocent in the midst of vipers. His aversion to certain papal trappings is seen as some kind of indicator that he is about to turn 2,000 years of authoritative church doctrine on its head.

In a scene that begs credulity, the character of John Paul I hints with all the subtlety of a ball peen hammer that he is going to do away with “Paul VI’s teaching” on artificial birth control. His reasoning is provided in purely secular language and thought process. He shows some cardinals a map of the developing world and tells them that tens of thousands of children are going to die unless the teaching on contraception is overturned.

The papacy of John Paul I, God rest his soul, was so short that he is forever encased in the “Smiling Pope” picture frame. To people with agendas, John Paul I becomes a human chameleon and turns whatever color he needs to be to fit a preconceived notion of who he might have been.

Saint John Paul II on the other hand, with his profound and lengthy papacy, gives those that are not the friends of the Church a target. In “The Last Confession,” the saintly pope gets the Pius XII treatment. He is branded as weak and immoral.

Spoiler Alert: John Paul II is revealed in the final act of the play as confessor to the troubled Cardinal Benelli. It is such a jarring caricature and infused with so much of the author’s own agenda that it’s unintentionally comical. The actor plays a hysterical John Paul II admitting to covering up the murder of John Paul I “for the good of the Church.” He insists that he would imperil his immortal soul to save the church.

“The Last Confession” views the Church through the prism of secular humanism. The audience obediently reacted to the actors’ choreographed language in audible scoffs at Church hubris and laughed at Church hypocrisy on cue. Contrary to the premise of this play though, popes do not rule by fiat. Humanae Vitae is not the personal teaching of Paul VI, but of the whole Church.

You can make a good play about corrupt churchmen. Robert Bolt did a profound job of that in “A Man for All Seasons” where, ironically, a man refused to imperil his immortal soul for King, country or the new Church of England.

If this libel against St. Pope John Paul II stands and people take for granted that he was implicit in the alleged murder of his predecessor — just as Pius XII is wrongly accused of evil behavior — I hope the author the “Last Confession” might consider a First Confession.

Robert Brennan has been a professional writer for more than 30 years, including many years in the television industry. He has been a contributing writer for the National Catholic Register for many years and has also been published in Our Sunday Visitor and This Rock.