Jean Painlevé (1902-1989) was an early visionary in the genres of educational, science and nature films. A three-disc set from Criterion, available on Netflix, is called “Science is Fiction: 23 Films by Jean Painlevé.”

In an introduction to “Science is Fiction,” editor Marian McDougall wrote: “The joy of experiencing these films, short cinematic gems that renew a sense of the mystery and miracle of nature, is to unearth a still fertile root of cinema and the revelation that there are film hybrids yet to be realized.”

The films, she continued, include “anthropological accounts that unfold like fiction,” “painterly descriptions of technological processes,” “absurd juxtapositions,” “animated fables,” “city symphonies” and “mechanical ballets.”

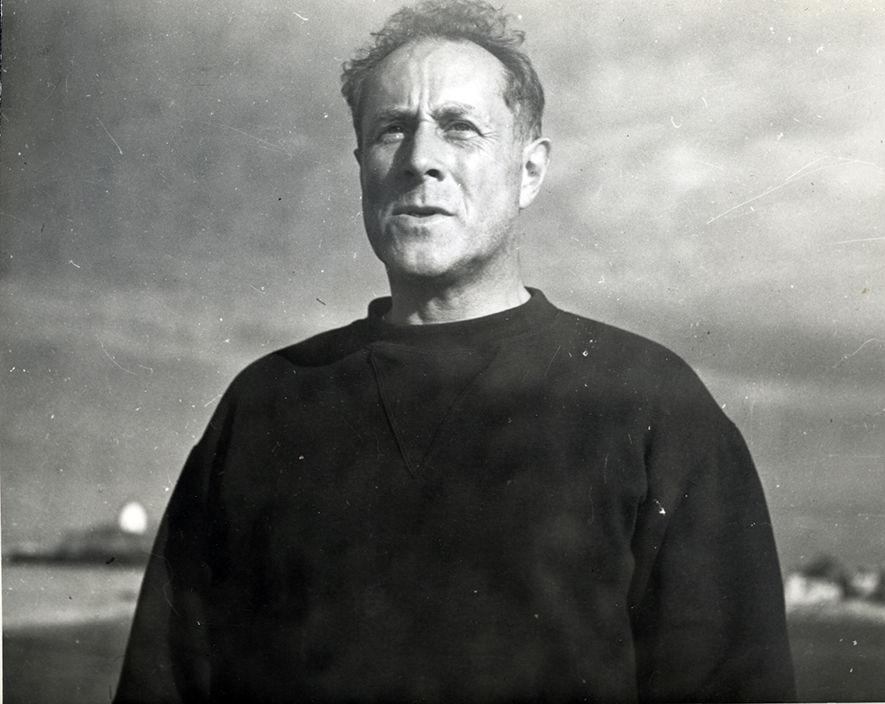

Painlevé was the son of a French prime minister and a mother who died two months after his birth. Well-educated and well-loved, he was also an outlier and a daredevil. “My only friends at school were Jews and outcasts,” he later remarked.

He took his first photographs at the age of eight, using the bottom of a glass bottle as a lens. As an adult, he befriended the Surrealists, raced cars and lived sans benefit of marriage with Geneviève (“Ginette”) Hamon, his lifelong helpmeet and collaborator.

But mostly he displayed an obsessive, single-minded love for creatures of all kinds — especially those of the sea.

His first film — “The Stickleback’s Egg: From Fertilization to Hatching” — debuted in 1928 before the esteemed Académie des sciences. One outraged viewer stormed out, crying, “Cinema is not to be taken seriously!”

Over the years, with extraordinary inventiveness he developed cameras, equipment, lighting sources and massive indoor aquariums to implement his work. He filmed jellyfish, liquid crystals and starfish larvae, magnifying them up to 1,400 times their actual size.

He scored his work with classical music and jazz.

He interposed poetry and humor with quirky text and eccentric narrators.

He saw the sea creatures as our brothers. From “Hyas and Stenorhynchus, Marine Crustaceans” (1929):

“He’s taken off to the police station.”

“An invitation to the waltz contains sinister motives.”

“Like all crustaceans, they are arm-wrestling enthusiasts.”

He emphasized what the narrator in one film calls “the grace and terror of gestures.”

He recognized that even at their weirdest and most absurd, the marine animals — like us — are somehow holy.

In “Sea Urchins” (1958), we learn that “At a certain magnification, their spines resemble the columns of a temple” and “Lit from behind, their jaws resemble a stained-glass window.”

As for the seahorse: “The pouting lower lip of its toothless mouth gives it a look of unease.” Small wonder. The male seahorse has a pouch in the front into which the female deposits 200 eggs in several batches. Five to six weeks later, he gives birth. “An anguished expression accompanies a rolling of his eyes. His body convulses and thrusts on the spot. His breathing speeds up. Finally, a massive contraction flattens the pouch, signaling that it’s time for the offspring to be released.”

In “The Love Life of the Octopus” (1965), we see this “horrific creature” as “it slithers, at low tide one tentacle after the other” and “white with fear, reacts to [the] female’s advances while keeping a prudent distance.” (Sound familiar, ladies?)

Of the wheezing narrator, Painlevé explained: “He was an old man who, out of vanity, refused to wear glasses. He was therefore obliged to stick his face right up against the script, where one could hear his emphysema.”

In “Acera or the Witches’ Dance” (1972), the acera, a kind of mollusk, wears a cloak that, during the mating dance, looks for all the world like a fluttering tutu. Aceras are hermaphrodites whose reproductive organs are in the neck. The animals often form chains of up to five, the frontrunner mindlessly eating mud while the two in the middle couple.

“The Vampire” (1945), set to a jazz score by Duke Ellington, begins: “Creatures in armor plating. Creatures strange and terrifying in form and movement. Living sculptures in priestlike garb. Frightening or graceful gestures. … Evil in the guise of complete and utter destruction.”

The scene where a Brazilian vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) coquettishly advances upon an unsuspecting guinea pig, makes a neat incision in its snout (the vampire’s “kiss”) and proceeds to drain it of blood was so disturbing I had to fast-forward to the next clip.

“When I was finishing the film,” Painlevé observed, “I noticed how the vampire bat extends its wing before going to sleep. I thought it looked like the Nazi ‘Heil Hitler’ salute.”

Sergei Eisenstein, the pioneering Soviet film director told Painlevé: “You alone stand as a competitor to Our Lady of Lourdes, as far as miracles are concerned.”

In a 1935 essay, “Feet in the Water,” Painlevé beautifully summarized his “theology.”

He wrote, “Wading around in water up to your ankles or navel, day and night, in all kinds of weather, even when there is no hope of finding anything, investigating everything, whether it be algae or an octopus, getting hypnotized by a sinister pond where everything seems to promise marvels although nothing lives there. This is the ecstasy of any addict.”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.