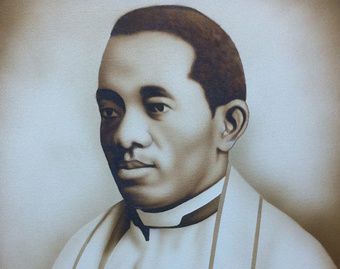

Black Catholics across the globe have dedicated their talents and their lives to their faith since earliest days of the Church, a Catholic author and scholar has said. “Black Catholicism is not something new. From the very first century, people of color have been involved in the universal Church,” Dr. Camille Brown, author of the 2008 book “African Saints, African Stories,” told CNA. “They have embraced the Universal Church with courage and with love of the Lord, just like everyone else.” Brown noted that this history dates back to events recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, where Philip the Apostle preached the gospel to an Ethiopian who “returned home rejoicing.” “We have scriptural evidence that the Gospel and the message of Our Lord Jesus Christ went to Africa from early on,” she said. “We have men and women of color from Africa who loved the Lord, who were martyrs for the Church and are definitely a part of our history. We cannot forget that it's nothing new,” Brown said. An associate superintendent of Archdiocese of Baltimore schools, Brown has also taught a course on the history of black Catholics at St. Charles Borromeo Seminary in Philadelphia. Brown's book lists “over 400 people of color who are identified saints.” Her own count exceeds 700 people, though she added that the racial identification of some saints is debated. “They were ordinary men and women just like us who just tried to love Jesus. Many were martyred,” she said. The first identified martyrs in Africa were St. Speratus and companions, while three Popes came from Africa: Victor I, Gelasius I, and Pope St. Miltiades. More recent black saints include St. Josephine Bakhita from Sudan, who was canonized in 2000. Born in what is now Sudan in the nineteenth century, she was kidnapped and sold as a slave multiple times before being bought by an Italian consul, who treated her well. According to her biography at the Vatican website, she returned to Italy with her owner and converted to Christianity, later joining the Daughters of Charity. Known for her sanctity and her Christian witness, St. Josephine Bakhita died in 1947. “What a beautiful story and what a beautiful testament to forgiveness!” Brown reflected. Black Catholicism has been particularly strong in some parishes and regions of the U.S. New Orleans has historically had a “strong pocket” of black Catholics, represented in part at Xavier University. It continues to have a strong presence today. Baltimore, the first diocesan see in the U.S., has had a “large nucleus” of black Catholics throughout its history. In Washington, D.C., St. Augustine Catholic Church continues to serve its historic role as a center for black Catholicism. Black Catholic history in St. Augustine, Florida dates back to its time as a Spanish colony where escaped slaves practiced the Catholic religion. Brown has also studied the lives of black Catholics she considers “saints in waiting.” These include Father Augustus Tolton, a former slave who became the first recognizable black priest in the United States before his death in 1897 at the age of 43. He had to go to seminary in Rome because no American seminary would accept him due to his race. “He had some job on his hands when he put that collar on and walked down the street and told people about Holy Mother Church,” Brown said. “What a job! I know that he suffered from that. He suffered greatly for it, and I believe went to an early grave for it.” Brown also praised the examples of Venerable Pierre Touissant, a former slave who lived a life of charity in 19th century New York City, and Ven. Henrietta DeLille, the New Orleans woman who founded the Sisters of the Holy Family. Servant of God Mary Lange, the Cuban-born co-founder of the Oblate Sisters of Providence, advanced religious and vocational education in Baltimore, Maryland. She taught black children at a time when they were not being educated. In 1828 she founded St. Francis Academy, which still continues operations in Baltimore. Brown said that black clergy and vowed religious “represented a beacon of hope for the community” and this role continues today. “They set out to show the role for black Catholics by making a contribution to the Catholic Church,” she said. “They set out to show that people of color are holy men and women, and that God has a place at the altar for all of us.” Brown saluted black clergy because of the challenges they faced historically and some still face today. “Not because they aren't smart enough. Not because they are not holy enough. God knows who he is calling to do his holy work. There may be some challenges there, racial challenges and otherwise, that these men are called to overcome. And they do.” Brown saw “plentiful and vast” opportunities for black Catholic leadership to emerge, especially in religious vocations. She said there is especially an opportunity for black Catholic families to “pull together and lead the way for other families.” Black Catholic families face many of the same cultural challenges posed by 21st century media and society. “Our Church is counter-cultural right now,” she said, “That’s a major, major, major challenge.” “We need our families so in love with the Church that they have to support their sons becoming priests and they have to support and advocate for their daughters to become religious sisters,” she urged. “We need our families so in love with Jesus and so in love with the Church that we are going to church together, sitting in the pews together,” she said. “We have to be at table praying, we have to be together saying our rosary. This is the time for us to pull our act together.”