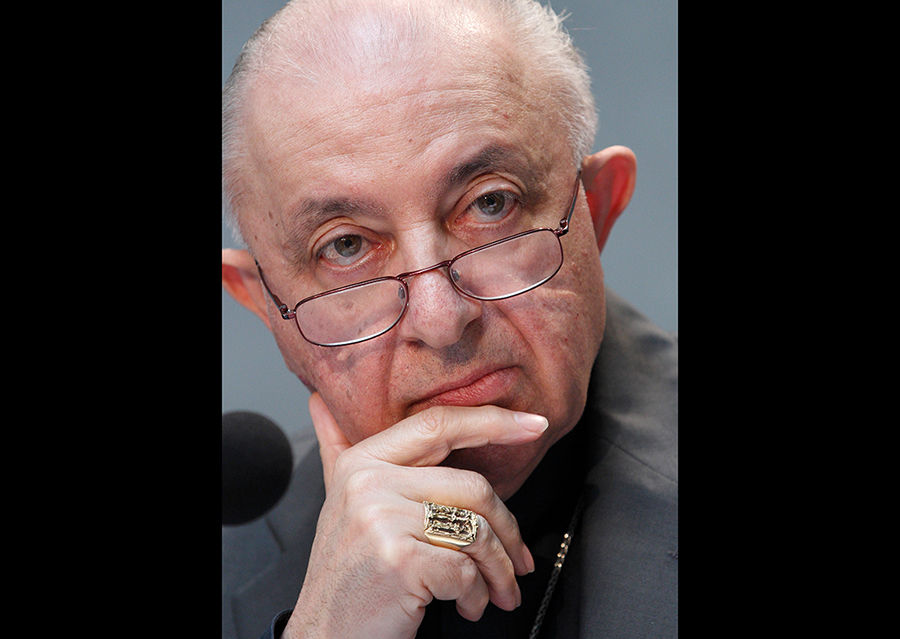

Italian Cardinal Dionigi Tettamanzi, who died on Aug. 5 at 83, was an important figure in Catholicism for most of his adult life, for a variety of reasons.

For those of us periodically called upon to handicap papal elections, however, Cardinal Tettamanzi is significant in yet another sense: he’s a permanent reminder that candidates who seem slam-dunk obvious, who check all the boxes and meet all the conventional criteria, can nevertheless basically vanish from consideration when the time comes.

In many ways, I’ve long thought of Cardinal Tettamanzi as the John Glenn of the Catholic Church.

Remember the brief Glenn boomlet back in 1984, when he ran for president? He was an authentic American hero, a former astronaut and a moderate Democrat who seemed ideally poised to take on President Ronald Reagan. To sweeten the pot, the popular movie “The Right Stuff” came out during the primaries, celebrating his heroism and providing countless millions in free public relations.

In the end, however, Glenn’s campaign went nowhere, the Democrats nominated Walter Mondale and they ended up on the wrong end of one of the greatest electoral college landslides in American history.

Similarly, I remember asking the late Cardinal Francis George of Chicago after the conclave of 2005, which elected Pope Benedict XVI, what his greatest surprise was. He said it was that alleged candidates who got a huge amount of buzz in the press, especially Cardinal Tettamanzi, had little traction once the cardinals actually got down to business.

Many Italians, naturally, see Cardinal Tettamanzi as confirmation of one of their best-loved sayings about papal elections: “Chi entra papa in conclave, ne esce cardinal” — meaning, “Who enters a conclave as pope, exits as a cardinal.”

The problem is that like so many bits of Italian conventional wisdom, it’s bunk half the time. Let’s take a look at the last seven papal elections to illustrate the point.

1939: The near-universal consensus was that the cardinal secretary of state, the Italian Eugenio Pacelli, was the overwhelming favorite. Had the Paddy Power betting agency in Ireland been keeping book at the time, the odds for Cardinal Pacelli probably would have been 2-1. In fact, Cardinal Pacelli was elected and went on to reign as Pope Pius XII for 19 years, leading the Church during the dark days of World War II.

1958: Heading into the election after the death of Pius XII, the overwhelming favorites were considered to be Cardinal Giuseppe Siri, a strong conservative, and Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro, a progressive-minded reformer. When it became clear that neither could generate a two-thirds majority, the cardinals turned to a surprise choice, Angelo Roncalli of Venice, who as Pope John XXIII called the Second Vatican Council.

1963: After the death of “Good Pope John,” the obvious choice to carry forward his council and his legacy seemed to be Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini of Milan, who was indeed elected after just six ballots, and who led the Church through the close of the council and its early implementation until 1978.

1978: The famous “Year of Three Popes,” the first conclave of 1978, in August, elected Cardinal Albino Luciani of Venice, who had been considered a favorite going in. Cardinal Jaime Sin of the Philippines actually told Cardinal Luciani before things got underway, “You will be the next pope.” When John Paul I died after just 33 days in office, the cardinals assembled again, and this time they chose a wild card: Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Kraków, Poland, who as Pope John Paul II went on to reign for almost 27 years.

2005: To take over from John Paul, the obvious “continuity” vote was German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who, as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, had been the intellectual architect of John Paul’s papacy. In many press accounts in the run-up, the choice was styled as Cardinal Ratzinger vs. Cardinal Tettamanzi, although, as noted above, that never really materialized. Cardinal Ratzinger was chosen, and put in eight difficult years as Pope Benedict XVI.

2013: After Benedict became the first pope in centuries to voluntarily resign the office, the conclave turned to Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina. Though he may not have been on many handicappers’ “A” lists, Cardinal Bergoglio wasn’t a complete stunner either, as he was in effect the runner-up to Cardinal Ratzinger eight years before.

Scorecard:

Frontrunners: 3

Middle of the Pack: 2

Total Surprises: 2

In other words, looking back over recent experience, the conclusion would seem to be that conclaves really aren’t all that different from other electoral exercises — sometimes front-runners win, and sometimes they don’t.

(By the way, if you discount for John Paul I, a 33-day papacy unlikely to repeat itself anytime soon, the average length of these modern papacies has been 14.8 years, which seemingly offers reason to believe that Francis may go on a good while longer.)

Although there’s absolutely no sign today that a papal transition is imminent, it’s easy enough to identify who the obvious candidates would be should one become necessary soon.

If you’re inclined to vote “continuity” with Pope Francis, you’d probably be looking at Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the pope’s secretary of state; Honduran Cardinal Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga, coordinator of his “C-9” council of nine advisers; Cardinal Sean O’Malley of Boston, a member of the C-9 and a prelate with a reputation as a reformer, especially on the sexual abuse scandals; and Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle of Manilla in the Philippines, more or less the “Asian Francis.”

If you think a slight course correction is in order in a more traditional direction, you’d be looking at Cardinal Robert Sarah of Guinea, currently the Vatican’s top liturgical official; Cardinal Péter Erd≈ë of Hungary, former president of the Council of the Bishops’ Conferences of Europe; Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith of Sri Lanka, a former Vatican liturgy czar; and, perhaps, Canadian Cardinal Marc Ouellet, prefect of the Vatican’s Congregation for Bishops.

If you think a compromise between those two currents is just what the doctor ordered, you’d probably be inclined to look at Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna, Austria, who was once Cardinal Ratzinger’s dauphin, and is today a key intellectual defender of the Pope Francis agenda.

The Tettamanzi lesson is this: Sure, take those guys seriously, because sometimes the obvious choice comes through. On the other hand, also take them with a grain of salt, because other times the obvious can become the implausible awfully quickly.