Now that the funny green hats, the green beer and the green everything else have been put away and the stores ready their shelves for the Easter Bunny, it’s time to recall an Irish heritage in the United States wedded for all time to the Church.

The Irish in New York in the middle part of the 19th century lived like they were in a Martin Scorsese film without the element of redemptive saving grace. Come to think of it, every film Martin Scorsese has ever directed is sans redemptive saving grace — but that’s another topic.

The squalor, despair and violence of the Irish existence in New York in the 19th century was so pervasive it is no wonder Scorsese found the subject impossible to resist, as his 2002 film “Gangs of New York” demonstrates.

In that film, we get a full frontal exposé on the vile existence of tens of thousands of Irish immigrants in New York and the Five Points section of the city, which was ground zero for gangs, murder, rape, prostitution and any other vice or crime human beings engage in.

The Irish had escaped the tyranny of British domination and found themselves slaves again to abject dissolution of any semblance of decent social contracts. Most of the people in jail at this time were Irish, most of the out of wedlock births were Irish, most of the prostitutes were Irish — the list goes on.

Even today, the ethnic slur of “paddy” lives on as you can still hear a police van used to transport criminals referred as a “paddy wagon.”

This toxic tonic flies in the face of the stereotypical “happy go lucky” Irish trotted out every March 17. Their Homeric levels of anti-social behaviors, coupled with the 19th century’s great American past time of nativism, seemed to condemn the Irish once and forever to zero class status.

They were characterized literally as apes at worst and drunken pawns of scheming clerics at best in all the best magazines and newspapers of the day. In short, they were a hot mess and it would have to take a miracle to turn things around. In the end it took a miracle worker named John Hughes.

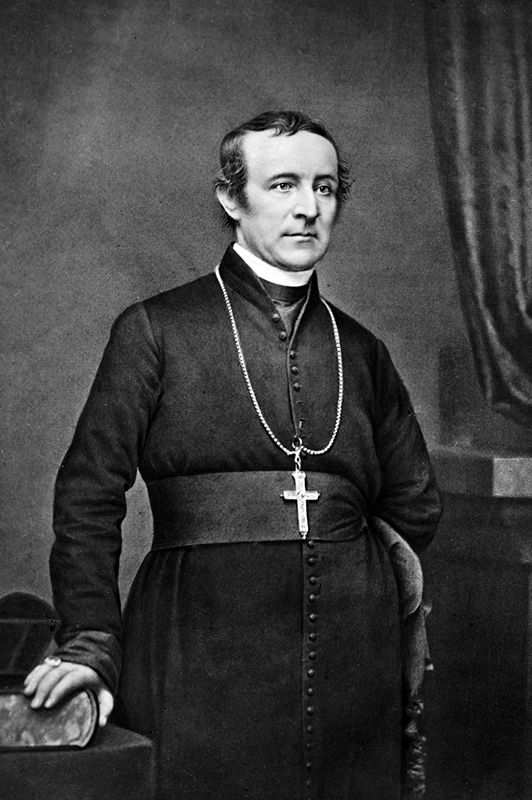

Like most great men, John Hughes was a jumble of contradictions. He was humble yet he vainly wore a toupee to cover his baldness. He was compassionate, but combative — you don’t earn the name “Dagger” John for nothing. He was born in poverty with little formal education, yet rose to the rank of Archbishop of New York.

He is one of the most important clerics in U.S. Catholic history that nobody remembers. His life reads like a movie, just not a Martin Scorsese movie.

Born in poverty in Ireland in 1797, he immigrated to America with his family when he was 20. One of his lasting memories of the “Auld Sod” was attending his sister’s funeral where the priest, by British edict, was not allowed to enter the cemetery during the rite of burial.

John had to get a handful of blessed dirt from the priest on the other side of a brick wall and carry it to his sister’s open grave.

In Maryland he landed a job as a gardener at Mount St. Mary’s College and Seminary. It was here his lifelong pull toward the priesthood took hold, but he was denied entry due to his lack of education.

In a turn of events that can only be construed as providential, John’s path crossed that of Mother Elizabeth Bayley Seton (America’s first saint). She saw something the head of the seminary did not. A woman already known for her persuasiveness, Mother Seton prevailed over the head of the seminary, convincing him to give Hughes a chance and soon he was on the road to priesthood.

His intelligence and natural born leadership qualities made him a star cleric of sorts. First in Philadelphia and then in 1838 John Hughes became the coadjutor-bishop in New York due to the illness of the current bishop, who just happened to be the same priest who had first rejected him for the seminary.

The population of New York at the time was 300,000, nearly 60,000 of which were Irish Catholics and almost all of them were either mired in poverty, menial labor or were participants on the wrong end of the legal system.

At the time, the only education option for Irish were “public” schools that instructed students in an American form of Protestantism friendly to neither Irish or Catholic sensibilities. Bishop Hughes battled this challenge by developing a Catholic school system that would help bring some structure, stability and promise for his wayward flock.

Like today, poverty in New York in the 19th century had a peculiarly feminine aspect. Many hard working decent Irish men moved on after their first stop in New York headed west to build railroads. Women and children mainly stayed behind with the less ambitious Irish men who sunk deeper and deeper into moral disrepair.

Bishop Hughes was brutally realistic about the Irish situation in his diocese.

“The destitute, the disabled, the broken down, the very young and the very old, having reached New York, stay. Those who stay are predominantly the scattered debris of the Irish nation.”

Just when things began to look up, 1845 happened. And things were about to get a whole lot worse for the Irish and for Bishop John Hughes.

Robert Brennan has been a professional writer for more than 30 years, including many years in the television industry.