“E. Charlton Fortune: The Colorful Spirit” is on view at the Pasadena Museum of California Art (PMCA) through Jan. 7, 2018.

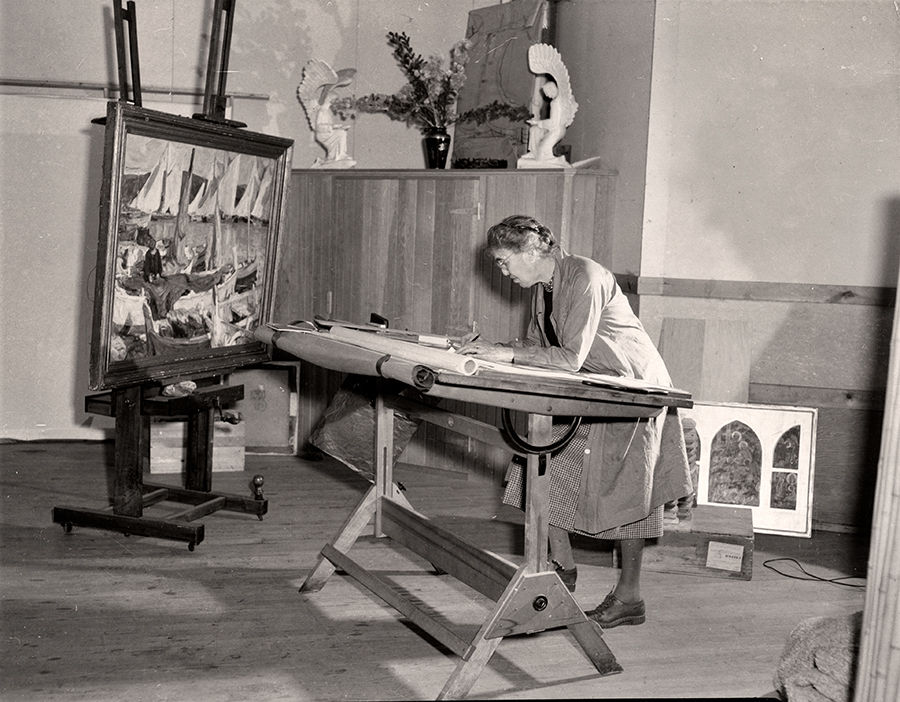

The exhibit (comprised of approximately 80 works) was curated by Scott A. Shields, Ph.D., California art scholar and associate director of Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum.

Notes Shields, “In the early to mid-20th century, E. Charlton Fortune was one of the most important California artists, male or female. The fact that she was a woman working at a transitional moment and in an atmosphere that still discouraged female professionals makes her achievements all the more extraordinary. No one disputes her standing as one of California’s most prestigious artists.”

Fortune (1885-1969) was born in Sausalito and named Euphemia; her friends would know her as Effie. Like her father, she had a cleft palate: a condition for which reconstructive surgery was not yet available.

She experienced many other traumas. Her father died when she was not yet 10. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed the Fortune family home, almost all of her paintings and the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art, where she had studied.

Possibly to shield herself, she developed a strong personality and a wry sense of humor. She never married.

She was further formed at the Art Student’s League in New York. Then she traveled widely, to the Monterey Peninsula, to the family’s ancestral home in Scotland, to St. Ives, England. Along the way, she developed a body of work that was roughly classed as Impressionistic — “Feeding Chickens,” “Picking Apples (later “Above the Town”),” “The Lonely Shore.”

During the 1920s in St. Tropez, she produced some of her finest and most strikingly “modern” works. The vivid colors — vermilion, turquoise, saffron yellow — are shot through with magic-hour Mediterranean light. Those strong colors, along with the rugged outlines and bold forms that characterized her paintings, led many to assume that Fortune was a man.

A lifelong, ardent practicing Catholic, Fortune eventually settled in Monterey, on California’s Central Coast.

In 1928, at the age of 43, her vocation took a radical turn. Frustrated with the poor quality of mass-produced ecclesiastical art, she founded the Monterey Guild. Under her direction, this group of skilled craftspeople designed modern artwork for churches throughout the country, including paintings and furnishings.

In 1942, she completed the design for the Sanctuary Mosaic in the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Kansas City, Missouri, later receiving the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice, a gold medal from Pope Pius XII for the work. From 1947-48, she was artist-in-residence at Portsmouth Priory (now Portsmouth Abbey) in Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

In the early 1950s, she received a commission from the Sisters of Providence in Oakland, California, for their Providence Hospital Chapel. The result was “The Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary.” All seven paintings, beautifully simple and deeply human, are included in the PMCA exhibit.

Many of her ecclesiastical works have since been removed or destroyed in the name of “renovation.” Fortune died in Carmel in 1969, at the age of 84. Her paintings now routinely fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Steve Hauk, of the Monterey gallery Hauk Fine Arts, has posted an instructive 11-minute YouTube lecture on Fortune’s life and art.

He said, “I read recently in ‘The Book of Tea’ [a 1906 essay on Japanese culture and aesthetics by Okakura Kakuz≈ç] that great paintings and plays and novels often leave a little for you to fill in. … They don’t connect all the dots. Fortune was that way. Her great Impressionistic work is a little vapory. The colors are gorgeous, but she doesn’t fill in all the details. When she did landscapes with figures, she basically left the face blank.”

Hauk also wrote a play called “Fortune’s Way, or Notes on Art for Catholics (and Others)” (2009). He has Fortune saying:

“The ability to paint superbly well … say, a lemon on a plate … as Manet can do so beautifully, is the best preparation for any religious subject.

“I mention this in a lecture I give in a seminary and …

(Pauses a beat; smiles.)

“… shock one of the students … scandalized, I think, my discussing God in conjunction with a lemon.”

That sense of Incarnational mysticism imbued both Fortune’s Impressionistic paintings and her liturgical art. All of her work was thus from and for God.

Today, as in her time, many are frustrated with the poor quality of ecclesiastical art. We can take a page from Fortune, who was prompted to make the turn in her vocation by a 1925 conversation with Dominican cleric Bede Jarrett.

As she lamented the frilly altar coverings and fussy Victorian bric-a-brac at the churches were she attended Mass, Jarrett challenged: “Why don’t you stop talking and do something about it?”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.