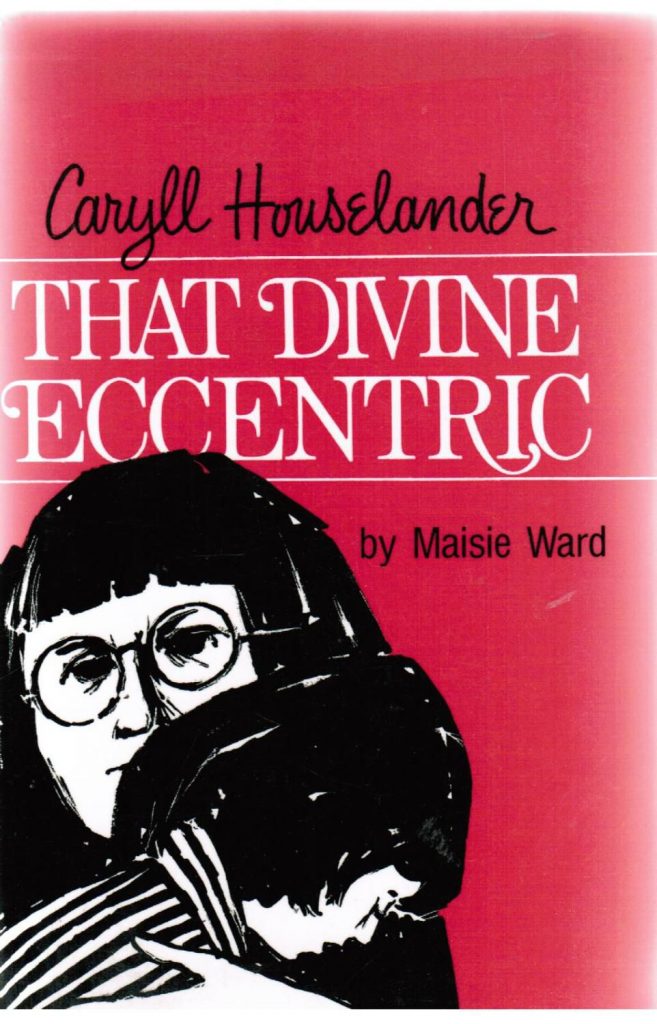

Caryll Houselander (1901-1954) was a British mystic, poet and spiritual teacher who wore a pair of big round tortoiseshell glasses, lived in London during the Blitz and, until she died at 53 from breast cancer, apparently barely slept or ate. A friend observed: “She used to cover her face with some abominable chalky-white substance which gave it quite often the tragic look one associates with clowns and great comedians.”

“That Divine Eccentric,” Maisie Ward’s fine biography, charts Houselander’s difficult childhood, her reversion to the Church in 1925 and her unrequited love for a British spy who would be the model for Ian Fleming’s “James Bond.” She had an eclectic coterie of friends. She never married. And she was utterly devoted to Christ.

Ward writes, “The sure cure for bitterness, Caryll comments, is to pray and do penance for the person: love will grow in proportion. ‘It is not according to how much penance I do or how many prayers I say, but how much love I put into it.’”

She became a prolific and popular author. Her works include “The Reed of God,” “A Rocking-Horse Catholic” and “The Risen Christ.”

“Guilt” (1951) contains passages on the mental suffering, among others, of serial killer Peter Kürten (“The Monster of Düsseldorf”), Hans Christian Andersen, Arthur Rimbaud and St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

From the dustjacket: “Caryll Houselander lives on the top floor of a high apartment building. Her rooms are color-washed, bare but for the essential furniture, many books and two or three gleaming icons: the windows look out on a view of the city. As well as writing, Miss Houselander’s interests include working with children, wood carving, drawing and painting, and the study of Jungian psychology, Hebrew and Russian spirituality.”

Houselander suffered greatly during her own life: from poverty, from frail health, from neuroses. She had a lifelong and especially deep and tender bond with traumatized children, and loved teaching them how to draw, paint and carve small animals out of wood.

One of her books is especially relevant during Advent: “The Little Way of the Infant Jesus” (former titles: “Wood of the Cradle, Wood of the Cross” and “The Passion of the Infant Christ”).

“Bethlehem is the inscape of Calvary,” she observes, “just as the snowflake is the inscape of the universe.”

She is never sentimental or soft:

“Everything felt by an infant by everyone in whom human nature is not dead is a dim reflection of God’s love for the world. All that grace and miracle of sustaining love in us is His shadow in our soul. We are made in His image and likeness, be we have almost obliterated, almost effaced, His image in us by the grotesque travesties with which we have overlaid it. In the presence of infancy man is restored to the image of God.”

But always, she comes around to the tenderness of Christ, and to the knowledge that we serve him in the small, hidden tasks of our daily life:

“Not only those parts of life that are difficult and painful, but joy, too, is our Christ-life. If we see with His eyes, we see the loveliness of this earth, of skies and water and flowers and stars, with a vision and sensitivity unimaginable otherwise. If we work with His hands, there is no work that is without dignity; whether it is a sheet of typing, scrubbing a floor, making a pie, doing a page of figures, carving a statue, playing the piano, or anything else, it is the work of Christ’s hands. It would be incredible if people, knowing that they work with His hands, did any work that is shoddy and careless, or is not the best that they can do; whatever they make will be warm and living from their touch.”

Houselander was not perfect. She swore and drank. She had a sharp tongue. She was also besieged by the emotionally wounded, the unbalanced, the petulant, quarrelsome and needy: she tried to be Christ to each of them. Perhaps that is why she has become a dear and treasured companion on my own spiritual path.

The novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald once famously observed, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”

Perhaps the test of a first-rate heart is the ability to connect two ideas that, while not necessarily opposed, are seemingly unrelated. For instance, these two quotes from Houselander:

“I am sure, as never before, that the Russian idea of Christ, humble, suffering, and crowned with thorns is the only true one; that it is impossible to be a Christian unless the humility of poverty of Christ is taken literally and all that tends towards power, grandeur, success and so on, is avoided and despised.”

And: “I think all teddy bears need knitted suits.”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.