I hadn’t been to Holy Cross Cemetery since I visited my younger brother’s grave many years ago. Hidden from the view of the 405 Freeway, it was here that we brought the body of my father-in-law, his final trip to Culver City, the town that first welcomed him so many decades before.

When we pick out grave sites, we often think in terms of the deceased. We want our last decisions regarding our loved family member to be to his satisfaction. And Joseph Bischetti would have liked this place. He would like the sloping hill, the tree standing at attention nearby, the view. Joseph was a man of the soil, and he wanted to be planted back in the soil.

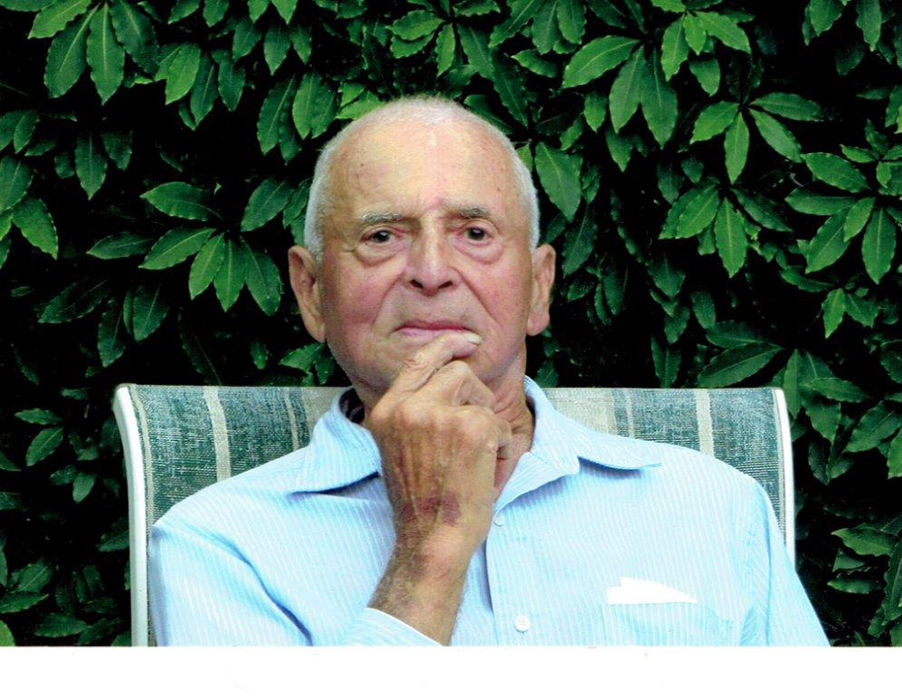

The son of poor farmers in France — themselves refugees from Mussolini’s fascists — he was a strong, courageous, intelligent working man who took that extraordinary leap of faith that is emigration. He traveled from France to French Algeria to California with boundless energy for work and little else.

In all our talk about immigration, we can overlook the fact that it takes a special kind of courage to pick up and relocate to a new land. Joseph only visited his family back in Europe twice, a source of regret in his later years. Times may be better now than when Joseph arrived. International travel is easier. The Internet connects us via Skype and Facebook. This isn’t the only sacrifice an émigré makes, however. To raise a family in a new land means coming to realize that there will always be a gulf of sorts between parent from the old world and child of the new.

When Joseph Greg up in France, his father and mother would talk to him in Italian, and he responded in French. When he spoke with his children in California, he often spoke in French and they answered in English. This is more than just a linguistic divide. It is a divide between the pioneer and the native.

The music, the friends, the hobbies, the aspirations may all be foreign to the pioneer and absolutely ordinary to the native. The parent who made so many calculated gambles in the search for a better life may not understand that his children are taking brave risks as well, even if they are of a different order: majoring in the liberal arts, not science. Choosing a career path that is not obvious nor has many guarantees. Even leaving the city and the state that he determinedly chose to embrace.

Yet the children of immigrants very often do not fall far from the tree. They have seen their parents make great sacrifices, and they are often the recipients of those values of hard work and discipline.

Joseph’s children saw their father build a business as a general contractor. He built for them the first house they owned. He put all four children through college, an experience he was never allowed to have. At age 80, he put a new roof on his house. By himself. He invested in Los Angeles in so many ways, the embodiment of the American dream at a time when so many of the natives have become cynical and tired and even disbelieving that such dreams are still possible.

Joseph loved Los Angeles, embracing the Mediterranean feel of its coastal climate. He grew tomatoes and fava beans, oranges, lemons and olives, channeling his own father’s aspirations perhaps. In his backyard, he tilled the soil under towering Eucalyptus trees swaying in the bay breeze, and he looked out over a canyon where Native Americans once wended their way down to the shore.

Not every immigrant is a hero, of course, and every generation of newcomers has had its share of what our president awkwardly calls “bad hombres.” The few do not represent the whole, however, and giving disproportionate attention to them is to miss what is really important.

My father-in-law is a reminder of how proud we Americans should be that so many of the bravest and most ambitious want to come to our land and want to participate in our 200-year-old experiment. Not just participate, but enrich. Like the silt-heavy waters of the Nile overflowing its banks and renewing the land it runs through, immigrants renew us. They renew our dreams and our aspirations when they arrive on our shores.

Los Angeles is poorer by one man today, but infinitely richer for what he left behind. I am proud of our welcoming Church that lets none of us forget that each human life has dignity and purpose, and that the richest asset of our city may not be the celebrities and business titans, but those newly arrived who, without complaint and without hesitation, make us better for having been in our midst.